Life at the Lake

a diary of living at a small lowland lakeWHAT IT'S LIKE

Early moonrise over Lake Ketchum

|

Archive Search |

| Links |

|

and s-integrator |

Another House Across The Lake

ATTRITION

It is an euphemism, of course, for loss, sometimes for death. Here on the lake, with 83 or so households, it is only natural that some people sell their homes and move away. People have changing requirements and time brings about—that word again!—attrition.

They come and go, people do. Life is change, said the wise guy. (Try it any other way and see what happens.) And we are not a close community; there are other lakes in the region, many of them, and the people are unable to get together, or unwilling, to form a lake association. Ours often seems tenuous. And some of that time it is quarrelsome and discordant. Yet we all have something in common, whether or not we wish to acknowledge it:

We live on a small lake and are part of an (ungated) community. We are connected, however fragiley, to one another by the lake we front on. The lake binds us together, though at times it seems to drive us farther apart. It is all we have in common. Often I wonder if it is enough.

Gary and Ida Andress owned a fine house on Lot 52, at least they did, in 2000. Then—for whatever personal reasons—they decided to sell and move away. I did not know them. In the Pacific Northwest we are not an overly friendly group of people. We do not get together socially, and when the lake experiences a crisis we meet I'd say unwillingly. So I know very few of the lake residents, though I probably know many more than most of the residents do.

Gary and Ida had a hard time selling their home. Perhaps it was overpriced; many people overvalue their property, at least in terms of market pricing. And it either sits or else the sellers have to come down in the price, sometimes down quite a bit. But after a couple of years the property did sell.

Down came the big For Sale sign on the side street. We waited to see who the new inhabitants would be. I lied a moment ago, when I said I didn't know the former owners: I had met I guess it was Gary in passing, and we had exchanged a few pleasant words. I told him I thought his home attractive, and it was. It has a hottub in a gazebo that permitted all-weather soaking—if that is your kind of thing. It wasn't mine. And he had a catamaran sailboat drawn up at a skewed angle on a gravely beach. Once or twice I had seen it out on the lake in the past six years. I though the Andress couple had looked slightly Hawaiian. Perhaps it was those flowered shirts.

The new people, according to our lake association records, are Ted and Jean Smith. (What an American-sounding couple of names, but I assure you I didn't make them up.) They moved in about a year ago. Ostensibly nothing much changed. The sailboat remains parked where it has always been, in the short reach of my memory. The hottub and its dark cedar housing. The waist-high cyclone fencing that hints at some dog in the house's past. The sense of decorum and quietude. There has been some bustle on both the West and East sides of the house. From the house itself not a stir.

We heard via the grapevine a couple of days ago that Ted Smith (his true name, I swear) died. What? Yes, he died, less than one year after buying and moving into the house.

I never knew him in the slightest and, of course, would not have recognized him if I had met him at Safeway or Hagens. So there is no matter of needing to say goodbye or to perform what they woodenly call today "closure." I know not Jean, either. Probably never will. Yet somewhere deep inside my lake-bound exterior something small sheds a tear at her husband's lack of fulfillment here. Did he dream, as I did, of life on a lake? Or was it just a place to hang his hat again, for a month or two short of a year?

For some questions there is no convenient answer.

- - Comments ()

...

One of the look-alike ducks, the Barrow's goldeneye

LOOK AGAIN

So many birds and ducks have two species that greatly resemble each other that it almost seems diabolically arranged. It is as though we set out to learn our "critters," and begin to, to some degree of effectiveness, when we learn what we've "learned" is wrong.

There are so many look-like ducks that the Audubon bird book, which consists largely of paired photographs, feels the need to place highly similar birds on the same page, one above the other, to help us out of our aviary consternation.

Viz., the wood duck and the Mandarin, the latter rarely sighted here; the hooded merganser male and its equivalent bufflehead; the American widgeon and its European counterpart, which do interbreed, of necessity, while the others don't, don't, don't.

This trait was brought to mind this morning (a bright sunny one, for a change) when I spotted out my breakfast window five lesser scaups, or so I thought. I know the species well enough that I do not bring up the field glasses to confirm what I detect visually unaided, that is, not most of the time. Only for special confirmations, or when I think I might be wrong.

I was wrong. There were five such ducks, all swimming in close proximity. One was female, the others males. One male hung a bit to the side, I noticed, but then that might have been the pathetic fallacy at work again, for I myself tend to such behavior. He looked identical, yet. . . .

Up came the glasses. He was a ringnecked duck. Such is life, I suppose, and of no matter, great or small. The margin of error is small, with ducks and other birds. Yet, how could I have mistaken him, even in bad light? And today the light was good.

He had the brilliant white band on his beak that—to continue to confuse matters—is not on his neck; there is no band I've been able to discern on his neck, and who ever originally named him had serious vision problems. Also, the gray in his body coloration was a little different from the scaups, just as the body coloration of the male common goldeneye varies from that of the Barrow's goldeneye.

But you have to have eyes to recognize the difference.

Maybe this will help. Daffy Duck—of lifelong comicbook fame—is a ringnecked duck. The pointed head of Daffy is a great aid in identifying him. The female scaup (either lesser or greater; it makes no difference) has no trouble making her selections in the mating department.

She will shun Daffy. (Poor guy!)

- - Comments ()

...

Blood Red Rhodedendron

We concern ourselves with trivia—flora, fauna, birds, ducks, fish—because that is one area in which we have some direct involvement and can affect the outcome. It is, admittedly, a cowardly response, but who can (or wants to) be brave today, when the world is in such turmoil?

And . . . what difference does it really make who we vote for for President, or whether or not we are in favor of the recent invasion of Iraq—a sovereign nation who evidently posed no military threat to us or housed no "weapons of mass destruction?"

We stay away from these topics because we cannot effect the outcome, even to a small degree. We came of age during the Fifties, that nervous and frightening period in which Senator McCarthy seemed to rule the country, and the FBI kept "enemies" lists of dissidents, that is, anybody who didn't agree that Communism and Russia were eminent threats to our democracy.

I served in the Army during the end of the Korean War; I had no choice. And when I was mustered out, I returned to graduate school, this time at Berkeley, where (Praise Be!) I was offered a job teaching Freshman English in the Extension School. On the GI Bill, I needed the supplement badly.

Before I could take the job, however, I had to sign a Loyalty Oath; it was so ordered by Chancellor Clark Kerr. What? True, I was but a few months out of the Army, where I had received a honorable separation from active duty, but my loyalty was being questioned, or, rather, I had to affirm it in writing before I could take the badly coveted job.

I hesitated for about forty seconds before putting down my John Handcock, not wondering whether Old John would have put his to such a document. And I got the job, which was only for one semester, and another, the following semester. Would I have, hadn't I signed? Of course not.

It was (is) a frightening time in terms of personal liberties. No Department of Home Land Security then, true, but the newly enacted one today brings back memories of those hard times. There is also The Patriot Act. And so we are cautious. Hell, we are scared. Some of our fear is based on possible repercussions.

Meanwhile Spring quietly advances. It rained all day yesterday. The trout continue to hit well in the lake and the rhododendrons are bursting out in riotous colors all over the yard.

The common big red one is a joy, and can be found in several locations here, even though its color is highly reminiscent of recently shed blood.

- - Comments ()

...

A Bass Bigger Than Last Night's

I do not catch so many bass that I am not astonished and delighted with each one that comes my way. In fact, I had never caught a bass until I moved to the lake. So they have always been special. Usually I catch one (rarely) when I don't intend to; when I set out to catch one, I don't. This is the wonderful serendipity of fishing.

Last night, just before dark, a three-pound largemouth came out from under my dock and grabbed my lure. I knew at once what it was, for bass fight differently, and when it was time to release it, I remembered that I could pick it up by its huge lower lip and, after a moment's shaking, it would remain supine in my grasp and I could work out the hook at my leisure. Which I did, with a little difficulty. Then I lowered Mr. Bass to the water and watched it quickly swim away.

It was a good short day, with three small hatchery trout and one holdover of probably just under three pounds that fought magnificently. (They named them "rainbows" because of how the good ones keep going into the air, where they shine.)

All fish were caught off my dock and released.

The trout are now actively feeding and their rings regularly spot the lake, exciting fishers and even those residents who don't fish, but know what they are seeing.The fish feed on a variety of natural foods—snails, scuds, and Chironomidae larvae making their way to the surface via a tiny air bubble that is attached to the egg sack. The surface of the lake is now often covered with midge flies newly hatched out. Fortunately, they are of the non-biting kind. They look a lot like mosquitoes, but do not whine or attack. Funny, but the trout do not rise for the adult, but happily feed on the larvae as they ascend, and when a ring appears on the lake (often, now) it is for the incidental sub-surface "take."

Most of the trout feeding takes place invisibly and, probably, constantly, for there is little nourishment in a single larva.

To me midge flies are a friendly nuisance and a vital part of the lake ecology. And they are an important food source for the fish I am after.

- - Comments ()

...

Earth Day Brings Forth Azaleas

Earth Day, 2003

I remember the first Earth Day in 1970. I was newly hired as Editor in Engineering at the University of Washington, at a time of protests against the war in Viet Nam. Angry students and others were occupying campus buildings and the Seattle police were a frequent presence on the Quad and elsewhere. Many of the same protesters were what was not yet called Greens. So Earth Day was just another demonstration, albeit one with a far different intention.

For me it was a holiday. Not a campus protestor, nor involved in an organization that had a program to celebrate this day, or one to march down I-5 to demonstrate against the war, I shut down my office, sent my secretary off to march (for she was more adamant than I), and took off for the Kalama River, some 135 miles to the South.

Fresh summer steelhead should be running in the lower canyon reaches of this fine stream, while all of ours to the North remained closed to protect the smolt migration, supposedly. (Why the ones to the South were not similarly protected soon became of concern to me.)

It was a beautiful day, bright and sunny and summer-like, though it had rained hard the previous night and well into the morning. There was a chance the river was full of mud. But, no, it wasn't. It was high and only slightly off-color.

Immediately I began catching fish, but they were not the mature, adult steelhead I was after, just the juveniles of the species—pretty little rainbow trout that ran 9-14 inches. Oversized, they took the fly well, and fought strongly, but they lacked the silver sheen and loose scales of the true steelhead smolt. Something was amiss here. The fishing was too easy, too good, to be true. The river was slowly rising and brown being added to the smoky green. I must have caught thirty fat trout before the water was too dirty to continue fishing and, besides, the trout had stopped hitting. I returned to my car and began to drive away, but stopped myself at the lower fish hatchery, where I saw some official-looking cars parked, that is, ones with Game Department insignias on the door.

I told the first employee I saw about my fishing experience. He laughed—a bit sadly, I thought—and explained what had happened. Through a bit of bad timing, the steelhead juveniles hadn't "smolted," that is, turned bright and silvery, ready for the transition to saltwater and the good life at sea, where they could eat plentifully and grow big and fast. They had retained their rainbow trout characteristics and it was doubtful whether, in the river, they would smolt and go to sea. Rather, they had "residualized," their term for it, and would hang around the river for their lifetimes, probably, vulnerable to fishers like myself and being taken home for a "trout" dinner. For all practical purposes of enhancing the summer steelhead run, they were a lost generation.

The river out of shape and my good fishing ended, I returned to Seattle late in the afternoon and caught the tailend of the First Earth Day celebration. The freeway had just opened up again in the opposite direction after the end of the war protest march, and traffic was now headed South successfully.

I decided to look in at the U, and saw a litter of discarded signs from the campus peaceful demonstrations. My office at Loew Hall was unlocked, the building deserted. Guiltily, I picked up some papers that didn't really need tending and headed home. I didn't touch them that night. Too tired from my trip. Earth Day (and I) have come a long way in those 33 years. So much has happened.

Much environmental legislation has been passed, including the Shorelines Management Program that requires setbacks or buffers on streams and lakes with anadromous fish running in them. And many of those rivers have now come under the threatened or endangered classification for Chinook salmon. This year—at least, yesterday—most of the streams around my lake remained closed, or have miniscule wild runs of steelhead that are hardly worth going after. So I contented myself with trout fishing on Lake Ketchum, my home. Yesterday I took four hatchery trout from off my dock, three of them on flies. I did not have to fish very long to do it. I consider myself fortunate. And the fish looked very much like those ancient Kalama River residualized steelhead juveniles. Though not so big.

- - Comments ()

...

Barrows in Flight, Picture Courtesy Claude Nadeau

Nature is full of surprises. Just when you think you finally know something for sure, and proceed with confidence, some new observation may leap right up and confound you with its fact. Then you will suddenly see how wrong you were in your everyday surmises and all the observations you take for granted.

Viz. Me and my ducks.

Earlier I wrote that there were two breeding pair of common golden eyes on the lake. These I recognized almost daily without the aid of binoculars. They have a readily identifiable silhouette and their behavior remains constant: they are often found in the shallows, where they neatly upend and descend for food.

The male and female are roughly the same shape, though he is a bit larger. She is drab, brownish, while he has a spectacular dark head, black and white barred body, and large white spot just below his eye. The head looks black, in a certain light, but reveals a greenish sheen, seen in another light.

Okay. So, yesterday, when in close to shore, repeatedly diving for short periods of time in search for whatever it is they eat—bits of weed, scuds, snails, small fish—one male looked slightly different, just enough to make me reach for the 10X binoculars (which are heavy and not much fun to use). The male was a Barrow's golden eye. I hadn't seen one in years, or, if I had, I hadn't separated this species of Bucephala from the other. (Shame on me.) And the female had a slightly different look, as well.

I marveled at the male Barrow's wondrous colors. Though I knew the bird's identity from former association, I went to one of my bird books for help. My male had the subtle markings of a duck in his first winter, where the telltale facial markings are faint. (She has a different beak coloration than a mature golden eye, but by then mine had drifted too far to the East to be able to make it out.) His head was less conical than the common's and his beak, and hers, shorter and less pronounced. It was like a visit from an old friend, though the concept of "friendship" was entirely mine.

Soon they swam a short distance away, and in that distance my eyes (newly awakened) could distinguish the other pair of golden eyes, the common (who are not all that "common"). How different they look, even at a hundred meters. How could I have ever gotten them confused?

It was not they who were confused, just I. And the Audubon book of birds pointed out, the birds do become slightly confused, but not for long, and it is the female who can distinguish the wrong kind of male, who may be in attendance, and discourage him. Ah, yes. It would be the pathetic fallacy again to draw human comparisons.

The important thing is, both species are friendly, but only up to a point. They share—both the woods where they will hatch then raise their brood and the watery world they will share with me.

And how important that is, in this other world of war and human misery.

- - Comments ()

...

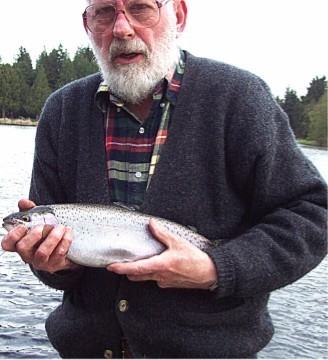

Nice holdover rainbow trout

Trout!

The lake was stocked a week ago tomorrow with one-thousand hatchery rainbows as part of the Department of Fish and Wildlife's enhancement program. This means the lake gets fished out each year and has to be replenished.

We who live here know that is not exactly correct. On a good year, and even on a bad one, there are a number of holdover trout from the previous year to provide good fishing for big fish, provided the fishermen don't kill them all off. This year we had a shortage of such fish, probably because visitors to the lake, and some fishers who live here, killed too many of last year's plant. So it goes. These are supposed to be catchable fish and are intended for consumption. Trouble is, nobody much likes to eat these small trout. And, if one likes trout to eat, they can be bought in most grocery stores, along with salmon.

I've caught half a dozen of the newly planted rainbows, so far, plus hooking and losing and releasing a few of the holdover, which go 14-20 inches. The females are darkening and are egg-bound, which means they have no place to spawn in our lake. A high percentage will die. A few will live on and become two-and-a-half or three pounders next year. In their prime they fight like steelhead. Which is saying a whole lot for them.

Last Monday, after they planted them, there was no obvious sign we had more fish. In fact, the holdovers stopped hitting. Tuesday was a slack day, too. On Wednesday, though they could not be seen feeding, they began to hit. I caught and released four, one of them a spunky holdover. I was surprised at how small the hatchery fish were, this year. A couple of inches shorter than last year. They looked like anchovies or minnows, and fought hardly at all. Well, that wasn't their fault, was it?

Next day, in the evening, they could be seen splashing. It takes a keen eye to spot their ring when the surface of the lake is broken by a breeze or the swallows are feeding on midges. Often the latter are mistaken for trout by those who do not look closely and see the swallows, who seem to hunt insects in packs, seemingly bouncing off the lake's surface, making a splash.

The trout, though not naturally occurring part of the biota, are an important contributor to the lake and one of its chief attractions. They will feed all spring and summer on the larvae of the midge flies, and those of the caddis and occasional mayflies, plus the tiny shrimp and larger snails on the bottom. They will grow at a rate of nearly two inches per month, which has always seemed to me near-miraculous.

In the meanwhile, until they get big enough to brag about, I will try to catch some of them, and will probably continue to complain about how small they are.

For I am at heart a steelhead fisher.

- - Comments ()

...